Software Supply Chain Failures (A03:2025): How One Compromised Dependency Can Destroy Your Organization

In-depth analysis of Software Supply Chain Failures covering vulnerable and outdated components, malicious packages, compromised CI/CD pipelines, dependency confusion attacks, real-world breaches including SolarWinds (18K organizations), Bybit ($1.5B theft), and Shai-Hulud worm, with practical SBOM, dependency scanning, and supply chain hardening recommendations.

Why the Community Ranked This #1 (Even Though It's #3 in Testing Data)

In the OWASP 2025 community survey, 50% of respondents ranked Software Supply Chain Failures as #1—the highest consensus of any category. Yet in actual testing data, it ranks lower. This paradox is telling: security professionals on the front lines see this threat as catastrophic, but automated testing consistently misses it.

The reason is profound: testing data looks backward at already-discovered vulnerabilities. Supply chain attacks are forward-looking threats from adversaries not yet caught. The gap between what we test and what's actually happening in the wild is exactly where this vulnerability lives.

A03:2025 represents OWASP's acknowledgment that the era of writing all your own code is over. Today, 80-90% of modern application codebases come from dependencies. Your attack surface isn't just your code—it's everyone's code you depend on, plus the build systems that combine them, plus the CI/CD infrastructure that deploys them.

What Happened Since 2021: From Component Vulnerability to Ecosystem Compromise

In 2021, OWASP called this "Vulnerable and Outdated Components." It was narrow: update your libraries. By 2025, the scope expanded dramatically. The new A03:2025 category encompasses all supply chain compromises:

Vulnerable and outdated dependencies (still relevant, but now just one part of the problem) Compromised CI/CD systems where attackers inject backdoors into officially signed releases (SolarWinds). Malicious packages seeded in registries like npm that use post-install scripts to harvest data and propagate automatically (Shai-Hulud worm 2025)

- Compromised vendor build environments

- Poisoned container images

- Tampered distribution channels

- Dependency confusion attacks where builds pull public packages instead of internal ones

- Malicious IDE extensions and developer tooling

This expanded scope reflects reality: attackers don't always target vulnerability. They target the path of least resistance. And right now, that path goes through the software supply chain.

Real-World Catastrophes: Why This Category Jumped to #3

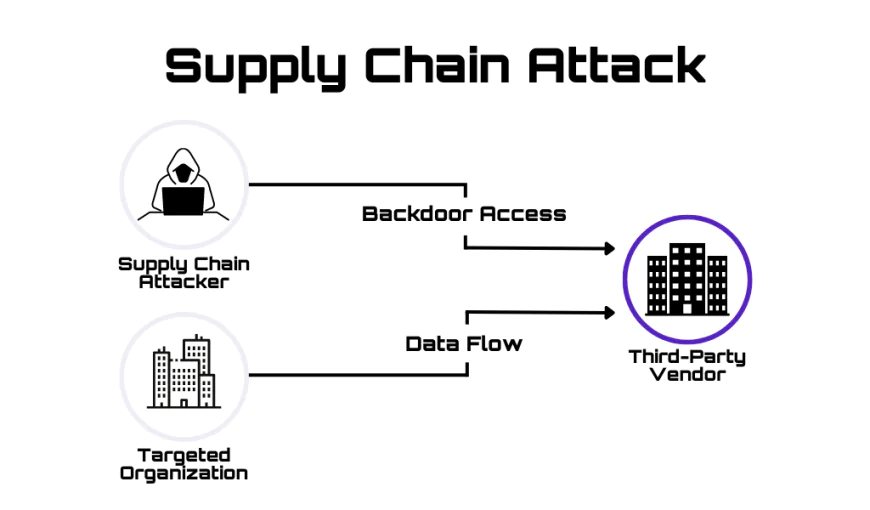

SolarWinds: The Breach That Changed Everything (2020)

Attackers compromised SolarWinds' build environment and injected backdoors into Orion software updates, leading to approximately 18,000 organizations being compromised.

This wasn't an obscure vulnerability discovered through code analysis. This was attackers gaining access to the vendor's own build systems and signing malicious code with the vendor's own certificates. Organizations didn't fail to update—they actively installed the malicious software believing it to be legitimate.

The impact was staggering: government agencies, Fortune 500 companies, and critical infrastructure operators all running backdoored software. The fix wasn't "update your libraries." The fix was "your vendor was compromised at the source."

Shai-Hulud: The First Self-Propagating npm Worm (2025)

Attackers seeded malicious versions of popular packages which used post-install scripts to harvest and exfiltrate sensitive data to public GitHub repositories. The malware would detect npm tokens in the victim environment and automatically use them to push malicious versions of any accessible package.

This attack is evolutionary. It's not just one malicious package—it's a worm that uses legitimate developer credentials to spread itself to additional packages. Each developer who installs the malicious package becomes a vector for infecting more packages.

Bybit: $1.5 Billion Stolen Through Conditional Supply Chain Attack (2025)

The theft of 1.5 billion dollars was caused by a supply chain attack in wallet software that only executed when the target wallet was being used.

This demonstrates sophisticated attacker tradecraft. Rather than obvious malware that sets off alarms immediately, the malicious code was dormant and only activated under specific conditions. It bypassed detection because traditional security tools never saw the activation trigger.

Log4j: One Library, Cascading Chaos (2021)

A single logging library used by millions of applications contained a critical remote code execution vulnerability. The fix was simple: update. The problem was massive: Log4j is so embedded in enterprise software that tracing every usage takes months.

Organizations that patched immediately still struggled to verify they caught every instance. Some updates introduced new bugs. Others broke application compatibility. A single library created organizational paralysis across the tech industry.

Attack Vectors: Where Supply Chain Failures Happen

1. Vulnerable and Outdated Components

The classic problem: your application uses a library from 2014 that's no longer maintained. The library contains a vulnerability discovered in 2024. Your application inherited that vulnerability simply by depending on old code.

This happens because:

- Dependencies go unmaintained (developers stop updating them)

- Applications don't update regularly (quarterly patch cycles lag far behind zero-day exploitation)

- Transitive dependencies go unmonitored (your app depends on lib-A, which depends on lib-B, which contains the vulnerability)

2. Malicious Package Registries

npm, PyPI, and other package registries are trusted but human-managed. A compromised package maintainer account can push malicious code instantly to millions of installations.

Attack scenario:

- Attacker brute-forces or social engineers access to a popular package maintainer

- Attacker publishes a malicious version

- Within hours, thousands of developers automatically install the malicious version

- The attack propagates before it's detected

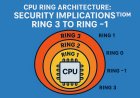

3. Compromised Build Pipelines

Your CI/CD system is where code gets built, tested, and packaged. If an attacker gains access here, they can inject malicious code directly into your artifacts.

This is especially dangerous because:

- Build systems are often less secure than production systems

- Artifacts built here are trusted and signed with legitimate credentials

- The malicious code is part of the "official" release

4. Dependency Confusion

Your internal build process is supposed to use your proprietary library "auth-lib" v1.0. But due to misconfiguration, the build system pulls "auth-lib" from the public npm registry instead.

An attacker publishes a malicious "auth-lib" to npm with a higher version number. Your build system pulls the malicious version. The attacker's code is now in your application.

5. Compromised Developer Tools

IDEs, extensions, and developer tooling are part of the supply chain. A compromised VS Code extension with millions of downloads can harvest credentials and SSH keys from developers' machines.

Testing Reality: Why 80% Detection Gap Exists

Supply chain failures have the highest average incidence rate at 5.19% but only 11 Common Vulnerability and Exposures (CVEs) having related CWEs. This creates a paradox: the vulnerability is everywhere but almost nowhere in official testing data.

The reasons:

- Automated tools scan for known vulnerabilities. Supply chain attacks often involve previously unknown malware or sophisticated conditional logic.

- Supply chain attacks span infrastructure that testing tools don't inspect: build systems, CI/CD pipelines, container registries.

- Social engineering and targeted attacks against specific organizations rarely appear in public vulnerability databases.

- Detecting supply chain compromise requires behavioral analysis and forensic investigation, not automated vulnerability scanning.

- Organizations rarely report supply chain attacks fully due to competitive concerns and customer relations.

How to Defend: From Visibility to Verification

1. Implement Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)

An SBOM is a detailed inventory of everything in your software: direct dependencies, transitive dependencies, versions, licenses, and known vulnerabilities.

Without an SBOM, you can't answer basic questions:

✅ What libraries does our application use?

✅ Are any of them vulnerable?

✅ Who maintains them?

✅ When were they last updated?

With an SBOM, you have visibility into your entire software composition.

Generate SBOMs automatically as part of your build process. Use tools like SPDX, CycloneDX, or commercial SCA platforms.

Store SBOMs centrally and update them with every build.

2. Continuous Vulnerability Scanning

Continuously monitor sources like Common Vulnerability and Exposures (CVE), National Vulnerability Database (NVD), and Open Source Vulnerabilities (OSV) for vulnerabilities in the components you use.

- Implement automated scanning that:

- Checks dependencies daily against latest CVE databases

- Alerts immediately when vulnerabilities are discovered in components you use

- Tracks remediation progress

- Escalates critical vulnerabilities to leadership

3. Secure Your CI/CD Pipeline

Your build system is as important as your application code. Harden it like you would production systems:

- Restrict access to build systems (principle of least privilege)

- Require multi-factor authentication for all build system access

- Audit all build system changes

- Implement signed commits and verified builds

- Scan build outputs for anomalies

- Separate build environments for different projects

- Use immutable infrastructure for build systems

4. Vendor Security Assessment

Before trusting a vendor or integrating their software:

- Request their SBOM

- Ask about their patch management process

- Verify their security practices

- Evaluate their incident response capabilities

- Monitor their security advisories

5. Dependency Verification

Only obtain components from official (trusted) sources over secure links. Prefer signed packages to reduce the chance of including a modified, malicious component.

Verify package signatures before installation. Check that cryptographic signatures match the publisher's known key.

Use package pinning to lock specific versions and prevent automatic malicious updates.

Scan downloaded packages for anomalies before installation.

6. Legacy Component Management

Treat legacy code as a first-class risk:

- Identify outdated components

- Prioritize remediation based on usage and vulnerability severity

- Consider replacement or retirement rather than patching ancient code

- Monitor legacy components even if unmaintained

7. Regular Patch Management

You do not fix or upgrade the underlying platform, frameworks, and dependencies in a risk-based, timely fashion. This commonly happens in environments when patching is a monthly or quarterly task under change control, leaving organizations open to days or months of unnecessary exposure before fixing vulnerabilities.

Implement risk-based patching:

- Critical vulnerabilities: patch within 24-72 hours

- High vulnerabilities: patch within 2 weeks

- Medium vulnerabilities: patch within 1 month

- Low vulnerabilities: patch within quarterly cycles

- Test patches for compatibility before production deployment

Regulatory and Compliance Implications

Supply chain security has moved from best practice to regulation. The EU Cyber Resilience Act and PCI DSS v4.0 now mandate supply chain security. Operators must:

✅ Maintain detailed SBOMs

✅ Respond to vulnerabilities within specified timeframes

✅ Document all patch management activities

✅ Prove supply chain monitoring and incident response capabilities

This isn't optional anymore. Compliance now requires demonstrable supply chain security practices.

Conclusion

Software supply chain failures are breakdowns or other compromises in the process of building, distributing, or updating software. They represent a fundamental shift in how software is attacked. Rather than exploiting individual application vulnerabilities, attackers target the infrastructure that builds and distributes software. One compromised dependency can affect millions of users globally.

The path forward requires visibility (SBOM), verification (signed packages), and hardening (secure CI/CD). Organizations that implement these practices dramatically reduce their risk. Those that don't will eventually appear in breach reports. Your software is only as secure as its weakest dependency. And with modern applications containing hundreds of dependencies, the math is simple: there are many weak links to exploit.