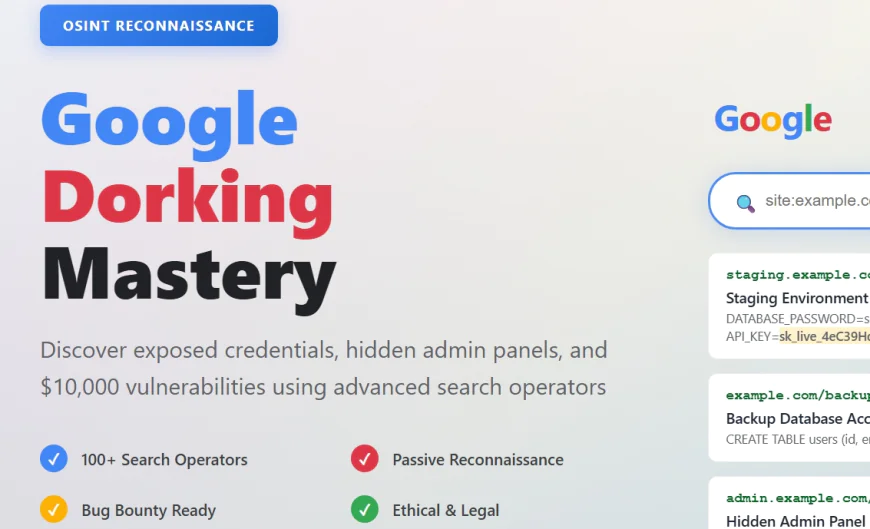

Google Dorking Mastery: From Passive OSINT to Finding Your Next $10,000 Bug Bounty

Master Google dorking from basics to advanced techniques. Learn passive reconnaissance using 100+ search operators, discover exposed credentials and configurations, find hidden admin panels, and locate high-impact vulnerabilities without touching the target server.

Google processes over 8.5 billion searches per day. The vast majority are ordinary queries. But for security professionals, penetration testers, and bug bounty hunters, Google is something far more powerful than a search engine. It's the world's largest index of publicly available information, and when weaponized correctly, it becomes an intelligence-gathering machine of unprecedented capability.

Google dorking, also known as Google hacking, is the practice of using advanced search operators to uncover hidden information that developers never intended to expose. This might include sensitive files, exposed credentials, hidden admin panels, vulnerable configurations, or entire databases accidentally indexed by Google's crawlers.

What makes Google dorking so powerful is its paradoxical nature. It's completely legal. It's entirely passive. You never touch the target server. You're simply using Google's search features as designed. Yet it consistently uncovers vulnerabilities that automated scanners miss and reveals information that would take weeks to discover through conventional reconnaissance.

A single well-crafted dork can reveal backup files containing database credentials. Another might expose configuration files containing API keys. A third could identify staging environments with security controls disabled. Skilled bug bounty hunters routinely find high-impact vulnerabilities worth thousands of dollars using nothing but carefully constructed Google queries.

This is the complete guide to mastering Google dorking.

Understanding Google Dorking: How It Works

Before exploring operators, you need to understand the fundamental principle: Google indexes everything that's publicly accessible unless explicitly told not to.

Developers can tell Google not to index content using robots.txt files or noindex meta tags. But countless sites either lack these controls or misconfigure them. A developer might accidentally expose staging environments to the public internet and forget to add robots.txt exclusions. A misconfigured server might serve directory listings where users can browse files directly. A backup script might create .bak files containing sensitive code and leave them in web-accessible directories.

These aren't exploited vulnerabilities in the traditional sense. They're exposures resulting from misconfigurations. Google's crawlers find them and index them like any other public content. By crafting specific search queries, you can find exactly what you're looking for among billions of indexed pages.

The power of Google dorking comes from its passive nature. You're gathering intelligence purely from publicly available sources. You're not scanning, fuzzing, or probing. You're not triggering intrusion detection systems. You're simply searching, exactly like any legitimate user would.

This passivity makes Google dorking ideal for the beginning stages of reconnaissance, where stealth is paramount. It's also ideal for responsible bug bounty programs where the scope explicitly excludes active scanning. You can conduct thorough reconnaissance without violating any program restrictions.

The Essential Operators: Your Reconnaissance Arsenal

Google dorking effectiveness depends entirely on understanding and correctly applying search operators. Here are the core operators every security professional must master.

site: Operator

The site operator restricts results to a specific domain.

Basic usage: site:example.com

This returns all pages indexed from example.com. Combined with other operators, it becomes extremely powerful. Finding subdomains:

site:*.example.com

site:*.*.example.com -www

The first command finds all subdomains. The second identifies second-level subdomains. This is critical for attack surface mapping. Finding specific directories:

site:example.com/admin

site:example.com/api

site:example.com/internal

This reveals potentially sensitive directories that might exist on the target.

inurl: Operator

The inurl operator matches search terms appearing in the URL itself. Common patterns:

inurl:admin

inurl:login

inurl:backup

inurl:debug

inurl:staging

inurl:.well-known

These often identify sensitive or administrative paths. Advanced combinations:

site:example.com inurl:backup

site:example.com inurl:test

site:example.com inurl:internal

This targets specific paths within the target domain, revealing forgotten or staging areas.

filetype: Operator

The filetype operator restricts results to specific file extensions. High-value targets:

filetype:pdf

filetype:xlsx

filetype:docx

filetype:env

filetype:config

filetype:sql

filetype:json

filetype:xml

filetype:bak

filetype:backup

Configuration files and database backups are particularly valuable. Finding sensitive documents:

site:example.com filetype:pdf "confidential"

site:example.com filetype:docx "internal"

site:example.com filetype:xlsx "credentials"

This targets document types while filtering for sensitive keywords.

intitle: Operator

The intitle operator matches text in the page title, which is often set by developers intentionally or accidentally to indicate content type.

Discovering common misconfigurations:

intitle:"index of"

intitle:"Apache"

intitle:"Directory listing"

intitle:"Nginx"

These often indicate directory browsing enabled, a serious misconfiguration. Finding login panels:

intitle:login

intitle:"admin login"

intitle:"user login"

Admin panels left accessible or improperly secured. Finding dashboards:

intitle:dashboard

intitle:console

intitle:control panel

intext: Operator

The intext operator matches specific text anywhere in the page content. Finding sensitive information:

intext:"password="

intext:"api_key="

intext:"secret="

intext:"token="

These often reveal hardcoded credentials or configuration exposures. Finding specific error messages:

intext:"SQL syntax error"

intext:"Fatal error"

intext:"Stack trace"

Error messages often reveal underlying technology and might hint at specific vulnerabilities.

cache: Operator

The cache operator returns Google's cached version of a page, showing how the page appeared when Google last crawled it.

cache:example.com/admin

This is particularly valuable for accessing pages that have since been removed or restricted, or for seeing if sensitive information was previously indexed.

link: and related: Operators

These operators identify pages linking to or related to a specific site.

link:example.com

related:example.com

These help with competitive intelligence, identifying integrations, or finding mentions in the broader web.

Advanced Operator Chaining: Crafting Surgical Queries

Mastering individual operators is the beginning. True expertise emerges when combining multiple operators into sophisticated queries that narrow results precisely.

Finding Exposed Configuration Files

The query: site:example.com (filetype:env OR filetype:config) -filetype:pdf

This finds .env and config files on the target domain while excluding PDFs that might create false positives.

Add keyword filtering: site:example.com filetype:env intext:"DATABASE" intext:"PASSWORD"

This finds environment files containing database credentials.

Discovering Staging Environments

The query:

site:example.com (inurl:staging OR inurl:test OR inurl:dev OR inurl:beta) -site:blog.example.com

This identifies staging or development deployments while excluding the blog subdomain (which might be out of scope).

Add title filtering: site:example.com (intitle:staging OR intitle:test) intext:"version"

Finding Git Repositories

The query:

site:example.com filetype:git

site:example.com inurl:.git

site:example.com inurl:.gitignore

Exposed .git directories can contain the entire repository history including deleted sensitive files.

Discovering API Endpoints

The query:

site:example.com inurl:api intext:"{"

site:example.com inurl:api/v1

site:example.com inurl:api/v2

This finds API endpoints that might be documented in error messages or cached pages.

Locating Database Backups

The query:

site:example.com (filetype:sql OR filetype:bak OR filetype:backup)

site:example.com inurl:backup filetype:sql

site:example.com filetype:sql intext:"CREATE TABLE"

Database backups can contain complete datasets.

Bug Bounty Specific Dorks: Finding Vulnerability Disclosure Programs

Not all dorking targets vulnerabilities in applications. Some targets the disclosure process itself.

Finding Responsible Disclosure Pages

The query:

intext:"submit your vulnerability" intitle:"bug bounty"

site:example.com intitle:"vulnerability disclosure"

intext:"responsible disclosure" site:example.com

These help identify which programs accept external vulnerability reports.

Finding Bug Bounty Halls of Fame

The query:

"bug bounty hall of fame" site:example.com

intext:"thanks" intext:"security researcher" site:example.com

These often list researcher names and vulnerability categories, providing intelligence about program scope and history.

Finding Security.txt Files

The query:

inurl:.well-known/security.txt

site:example.com inurl:.well-known

intitle:"security.txt"

The RFC 9116 security.txt standard provides standardized vulnerability reporting information.

Credential and Secret Discovery: High-Impact Findings

Some dorks specifically target leaked credentials, API keys, and other secrets.

Finding Exposed API Keys

The query:

intext:"api_key=" site:example.com

intext:"apikey:" site:example.com

intext:"Authorization: Bearer" site:example.com

filetype:json intext:"token" site:example.com

API keys might appear in documentation, error messages, or cached responses.

Discovering Hardcoded Credentials

The query:

intext:"password=" site:example.com

intext:"user=" intext:"password=" site:example.com

filetype:config intext:"username" intext:"password"

Database connection strings and application credentials sometimes appear in configuration files.

Finding AWS Keys and Cloud Credentials

The query:

intext:"AKIAIOSFODNN7EXAMPLE" (AWS key format)

intext:"aws_secret_access_key" site:example.com

intext:"google_api_key" site:example.com

Cloud provider keys represent critical infrastructure access.

Discovering Private Keys

The query:

"-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----" site:example.com

"-----BEGIN OPENSSH PRIVATE KEY-----" site:example.com

filetype:pem site:example.com

Private keys enable impersonation of services or systems.

Real-World Bug Bounty Dorks: Tested and Proven

These dorks have discovered actual vulnerabilities worth thousands of dollars.

Finding Information Disclosure

site:example.com filetype:pdf "internal" "confidential"

site:example.com inurl:backup filetype:sql

site:example.com filetype:xlsx "password" OR "secret" OR "token"

site:example.com intitle:"index of" filetype:zip

Discovering Misconfigured Infrastructure

site:example.com intitle:"index of /"

site:example.com intitle:"Apache" filetype:log

site:example.com inurl:upload filetype:php

site:example.com inurl:.well-known inurl:acme-challenge

Finding Hidden Admin Panels

site:example.com inurl:admin filetype:html

site:example.com inurl:administrator

site:example.com inurl:wp-admin

site:example.com inurl:cpanel

Locating Staging and Development

site:staging.example.com

site:dev.example.com

site:test.example.com

site:*.example.com inurl:staging

site:example.com intitle:staging

Identifying Vulnerable Technology Version

site:example.com intext:"Apache/2.4.1" (vulnerable version)

site:example.com intext:"WordPress 5.0" (with known vulnerabilities)

site:example.com intext:"PHP 7.0" (outdated)

Finding Error Messages

site:example.com intext:"SQL syntax error"

site:example.com intext:"Stack trace"

site:example.com intext:"Warning: MySQL"

site:example.com intext:"Fatal error in"

Ethical Considerations and Legal Requirements

Google dorking exists in a legal gray area that requires careful navigation. Using Google's search features is entirely legal. Google provides these operators intentionally. You're not bypassing security or hacking anything. You're using a publicly available tool as designed.

However, accessing or exploiting discovered information without authorization is illegal. If you find a file you shouldn't have access to, viewing it might constitute unauthorized computer access. Downloading it might constitute data theft. Exploiting it could constitute fraud or wire fraud.

The critical distinction is authorization. In bug bounty programs, the program scope explicitly authorizes reconnaissance. They're inviting you to use these techniques. You have explicit permission.

In penetration testing, the Rules of Engagement document specifies authorized actions. Google dorking against authorized targets is fine. Against unauthorized targets is illegal.

In bug bounty programs, always verify target scope. Some programs exclude passive information gathering. Some require no passive reconnaissance beyond the program website. Read the program rules carefully.

Always stay within scope. If API endpoints aren't in scope, don't dork for them. If staging environments aren't in scope, don't search for them. Program scope isn't just guidance. It's your legal authorization boundary.

Never access, download, or exploit information without authorization. If you find a database backup, don't download it. Report the finding. If you discover credentials, don't use them. Report them. The bug bounty is for discovery, not exploitation.

Always report ethically and responsibly. Provide the organization time to patch before disclosure. Follow the program's responsible disclosure policy. Never publicly disclose vulnerabilities before remediation.

Tools and Automation: Scaling Your Dorking

While manual dorking develops intuition and understanding, tools help scale reconnaissance.

DorkFinder.com

An interactive platform with categorized dorks, filtering capabilities, and result analysis tools. Useful for building custom dorks interactively.

Google Dorking GitHub Repositories

Several repositories maintain constantly updated collections of dorks optimized for various targets. These provide templates and starting points.

Advanced Techniques: Beyond Basic Operators

Boolean Logic and Grouping

Google supports basic boolean logic: (site:*.example.com OR site:*.example.co.uk) filetype:pdf

This searches multiple domain extensions simultaneously.

Negative Keywords

Excluding irrelevant results: site:example.com filetype:pdf -inurl:blog -inurl:help

This excludes blog and help sections that might generate false positives.

Wildcard Searching

The asterisk wildcards unknown terms:

site:example.com inurl:*admin*

site:example.com filetype:* "password"

Regular Expression Approximation

While Google doesn't support true regex, intelligent phrasing approximates regex behavior: site:example.com (inurl:backup OR inurl:backups OR inurl:back OR inurl:bak)

Time-Based Filtering

Using Google's Tools menu after a dork:

- Search your dork normally

- Click Tools

- Select Any Time > Past Year (or specific timeframe)

- This reveals recently indexed content, often indicating recent deployments or misconfigurations

Building Your Dorking Methodology

Effective dorking requires systematic methodology.

Step 1: Target Profiling

Understand your target before dorking:

- What technologies does the target use?

- What's the organizational structure?

- What domains and subdomains exist?

- What platforms does the target integrate with?

Step 2: Attack Surface Mapping

Create comprehensive dorking queries targeting all identified assets:

- Main domain and all subdomains

- All associated domains and extensions

- All technologies identified

Step 3: Vulnerability Class Targeting

Create dorks for each vulnerability class relevant to your target:

- Information disclosure (exposed files, configs)

- Authentication bypass (admin panels, test accounts)

- Access control (staging environments, debug modes)

- Misconfiguration (open directories, error messages)

- Credential exposure (API keys, passwords)

Step 4: Iterative Refinement

Analyze dork results and refine:

- If too many results, add negative operators or additional filters

- If too few results, broaden keywords or relax filters

- If irrelevant results dominate, adjust terminology

Step 5: Verification

Verify discovered findings:

- Confirm sensitivity level

- Ensure it's in scope

- Document the exact query and result

- Assess potential impact

Step 6: Responsible Reporting

Report findings with:

- Clear description of the exposure

- Exact discovery method (dork query)

- Evidence (screenshot)

- Remediation recommendation

- Timeline for expected fix

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake 1: Overly Broad Queries

Searching for common keywords returns millions of results. Always constrain with site: operator.

Mistake 2: Forgetting Negative Operators

Excluding irrelevant results (blogs, forums, documentation) dramatically improves efficiency. Use -inurl: and -site: liberally.

Mistake 3: Not Combining Operators

Single operators return too many false positives. Chain operators for precision.

Mistake 4: Ignoring Scope

Staying within scope is legal requirement and ethical obligation. Verify authorization before dorking any target.

Mistake 5: Not Documenting Findings

Save successful dorks, note what they discovered, and the timeline. Build a personal dork library.

Mistake 6: Accessing Unauthorized Data

Finding data is not authorization to access it. Report findings without exploitation.

Mistake 7: Assuming Dorks Are Exhaustive

Google dorking reveals only indexed content. Unindexed sensitive data remains hidden. Use dorking as part of reconnaissance, not the entirety.

Conclusion: Google Dorking in 2025

✅ Google dorking is simultaneously ancient and eternally relevant. The techniques predate modern bug bounty programs. Yet they remain among the most effective reconnaissance methods available.

✅ In 2025, as organizations increasingly implement automated security scanning and intrusion detection, passive reconnaissance becomes even more valuable. Dorks reveal information without triggering alarms. They're stealthy. They're legal. They're free.

✅ The most successful bug bounty hunters use Google dorking as the foundation of their reconnaissance. They develop intuition about what information exists and where it's likely to be exposed. They build personal dork libraries targeting common misconfigurations. They chain operators creatively to uncover vulnerabilities others miss.

✅ Your next high-impact vulnerability might be just one carefully crafted search query away. The skill isn't technical. It's intellectual. It's about understanding how developers think, where they typically make mistakes, and how to search for evidence of those mistakes.