China-Linked Hackers Exploit VMware ESXi Zero-Day Vulnerabilities to Escape Virtual Machines

China-linked threat actors exploited VMware ESXi zero-day vulnerabilities to escape virtual machines and compromise hypervisors, researchers reveal.

Experts in the field of cybersecurity have revealed a very complicated attack campaign where threat actors linked to China used various zero-day vulnerabilities in VMware ESXi to break out of virtual machines and take over the hypervisor. The firm Huntress identified the operation in December 2025, and it was terminated before it reached the final stage, which is thought by the analysts to have been a ransomware attack.

Such an occurrence points out a new development in the world of sophisticated cyber operations: the attacking of virtualization platforms directly rather than individual servers or endpoints indirectly. Attackers would have full control over all VMs if they took over the hypervisor and that would be a very impactful attack.

Initial Access via SonicWall VPN

As per Huntress, the attackers are believed to have first secured their position by means of a compromised SonicWall VPN appliance. VPN appliances are still deemed to be very appealing targets for malicious actors since they usually provide internal networks with privileged access and are often less monitored after installation.

The malicious intruders, who were already in the system, installed their own exploit kit quite stealthily from a guest virtual machine and then launched a well-prepared VM escape attack on the ESXi host.

VMware ESXi Zero-Day Vulnerabilities Exploited

The attack chain leveraged three VMware ESXi vulnerabilities that were disclosed as zero-days by Broadcom in March 2025:

-

CVE-2025-22224 (CVSS 9.3)

-

CVE-2025-22225 (CVSS 8.2)

-

CVE-2025-22226 (CVSS 7.1)

By integrating these vulnerabilities, an intruder with access to a VM's admin account can extract confidential memory from the Virtual Machine Executable (VMX) process, carry out memory corruption via the Virtual Machine Communication Interface (VMCI), and in the end, move out of the VM sandbox to run code on the ESXi hypervisor that controls the virtual machines.

As a result of the confirmation of their active exploitation, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) included these defects in its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog and recommended that companies implement the patches without delay.

Signs of Advanced and Early Development

The researchers from Huntress have revealed substantial evidence which points to the fact that the exploit toolkit was in the making for quite some time, possibly more than a year, even before it was made public. The debug symbols and embedded paths trace back to the development activity of late 2023, which means that the hackers were probably aware of the security flaws before the defenders even had any clue about them.

Moreover, the toolkit has a number of strings in simplified Chinese, one of which is the name of a folder that can be translated as "All version escape - delivery". The creator(s) of this exploit, who left no traces behind, must have belonged to a resourceful and technologically proficient Chinese-speaking developer.

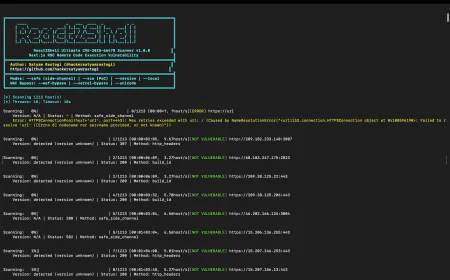

How the VM Escape Attack Works

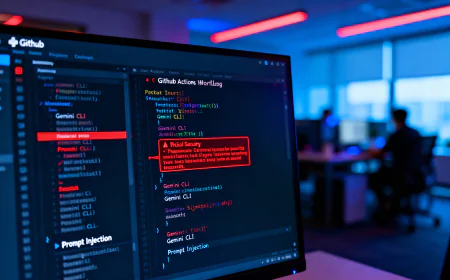

An orchestrator binary, named "exploit.exe" (MAESTRO), is at the heart of the operation, which manages the VM escape procedure. The toolkit uses a number of auxiliary components to set up and carry out the attack.

One of these components switches off the VMCI drivers that run on the guest side in VMware for a short time, and the other one loads an unsigned kernel driver into the memory through an open-source utility. This driver gets to know the version of ESXi that is running on the host and then activates the corresponding exploit path.

After the vulnerabilities have been successfully exploited, the attacker transfers several payloads straight into the memory of the VMX process. Among these are code to prepare the escape, to make a hook on the ESXi host, and to install a backdoor that survives the next reboot.

VSOCK-Based Backdoor and Stealthy Access

One of the main payloads that were using during the attack is a 64-bit ELF backdoor which communicates through VSOCK (Virtual Sockets) on port 10000. VSOCK is a direct communication channel between the guest VMs and the hypervisor and thus does not depend on the traditional network interfaces at all.

This whole thing makes the backdoor very stealthy as it does not generate the standard network traffic that is usually monitoring by firewalls or intrusion detection systems.

For the operating of the compromised ESXi host the hackers made use of a Windows utility called “client.exe” or the GetShell Plugin. With this tool, the attackers are able to run commands on the hypervisor, upload and download files as well as keep on doing assembly work. It should be noted that the tool comes with a README file that contains usage instructions, which means the toolkit was indeed meant for several parties and designed for operational use.

Targeted and Private Distribution

Even though the toolkit was highly sophisticated, researchers did not come across any trace of it being promoted in public underground forums. On the contrary, Huntress is very confident that it was sold to a small number of buyers and distributed in a selective manner, probably via locked channels. Such a monitored distribution practice is characteristic of high-quality offensive tools where the makers restrain their product's visibility in order to lessen the chances of being detected and to prevent the formation of broadly used security signatures.

Why This Attack Matters

The said campaign exhibits the manner in which advanced threat actors can circumvent the isolation of virtual machines, thereby making the hypervisor a principal target. The moment ESXi is breached, all the VMs operating on that particular host come under the control of the intruder.

The employing of a series of zero-days, early exploit development, and VSOCK communication with stealthiness all emphasize the continually changing threat scenario for the contemporary virtualized and cloud-based environments.

Conclusion

The zero-day vulnerability exploitation of VMware ESXi, discovered by Huntress, is a bitter pill for organizations that depend on virtualization infrastructure to swallow. It underlines the necessity of implementations like timely patching, VPN hardening, least-privilege access and enhanced hypervisor monitoring.

And since attackers are moving onto deeper layers of the infrastructure, defending the hypervisor has become a non-negotiable necessity for enterprise security.