System Architecture

A clear overview of Windows internal architecture: user mode vs kernel mode, executive services, HAL, hypervisor, subsystem DLLs, and how Windows achieves portability across x86, x64, and ARM.

In most multiuser operating systems, applications are separated from the OS itself. The OS kernel code runs in a privileged processor mode, with access to system data and to the hardware. Application code runs in a non-privileged processor mode, with a limited set of interfaces available, limited access to system data, and no direct access to hardware. When a user-mode program calls a system service, the processor executes a special instruction that switches the calling thread to kernel mode. When the system service completes, the OS switches the thread context back to user mode and allows the caller to continue.

Windows is not an object-oriented system in the strict sense. Most of the kernel-mode OS code is written in C for portability. The C programming language doesn’t directly support object-oriented constructs such as polymorphic functions or class inheritance. Therefore, the C-based implementation of objects in Windows borrows from, but doesn’t depend on, features of particular object-oriented languages.

Architecture Overview

A simplified version of this architecture is shown in Figure 2-1. Keep in mind that this diagram is basic. It doesn’t show everything. For example, the networking components and the various types of device driver layering are not shown.

First notice the line dividing the user-mode and kernel-mode parts of the Windows OS. The boxes above the line represent user-mode processes, and the components below the line are kernel-mode OS services.

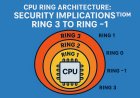

A second dividing line between kernel-mode parts of Windows and the hypervisor is also visible. Strictly speaking, the hypervisor still runs with the same CPU privilege level (0) as the kernel, but because it uses specialized CPU instructions (VT-x on Intel, SVM on AMD), it can both isolate itself from the kernel while also monitoring it (and applications). For these reasons, you may often hear the term ring -1 thrown around (which is inaccurate).

Technically, CPUs only define Rings 0–3.

What are Subsystem DLLs?

These are **user-mode libraries** that provide application-level APIs for Windows applications.

Examples:

Kernel32.dll → General system functions (memory, files, threads)

User32.dll → User interface functions (windows, messages)

Gdi32.dll → Graphics functions

Advapi32.dll → Security-related functions (registry, services)

Ole32.dll, ComBase.dll → COM support

Applications use these DLLs by importing their functions and calling their APIs.

What happens when an application calls an API?

CreateFile("C:\\test.txt", ...);Here’s what happens internally:

1. The application calls CreateFile, which is in Kernel32.dll.

2. Kernel32.dll translates this call into a lower-level native system call, like NtCreateFile.

3. This native call is implemented in Ntdll.dll (another user-mode DLL).

4. Ntdll.dll then performs a system call (syscall) — a transition from user mode to kernel mode — to execute the corresponding code inside the Windows kernel (e.g., in ntoskrnl.exe).

5. In some cases, Kernel32.dll or Ntdll.dll may also send a message to an environment subsystem process (like csrss.exe) if the request requires coordination with the subsystem.

The kernel-mode components of Windows include the following:

1 Executive

The Windows Executive is the core part of the Windows OS that implements base operating system services.

Responsibilities include:

- memory management

- process/thread management

- security enforcement

- I/O management

- networking

- inter-process communication (IPC).

It runs in kernel mode and is used by both the Windows kernel and device drivers.

2 Windows Kernel

The kernel is responsible for low-level foundational functions.

Handles

- thread scheduling,

- hardware interrupts,

- exception dispatching,

- multiprocessor synchronization.

Provides basic objects and routines used by the executive and other kernel-mode modules.

3 Device Drivers

Drivers act as translators between user-mode I/O requests and hardware devices.

Includes

- Hardware drivers (e.g. for keyboard, disk, USB)

- Software drivers (e.g. file system drivers, network stack, encryption).

4 Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL)

This is a layer of code that isolates the kernel, the device drivers, and the rest of the Windows executive from platform-specific hardware differences (such as differences between motherboards).

Allows the same Windows kernel to run on different motherboards/CPUs without rewriting the kernel.

- Handles

- interrupt controllers

- timers

- power management

- bus interfaces.

5 Windowing and Graphics System

This is the kernel-mode implementation of the Windows GUI subsystem.

Includes

- USER subsystem: Windows, buttons, messages, etc.

- GDI subsystem: drawing, fonts, rendering, etc.

These functions are implemented in the kernel module Win32k.sys.

In Windows, the GUI (Graphical User Interface) components run primarily in user mode, but some parts of it also involve kernel mode operations for performance and low-level access.

6 Hypervisor Layer

This is composed of a single component: the hypervisor itself. There are no drivers or other modules in this environment. That being said, the hypervisor is itself composed of multiple internal layers and services, such as its own memory manager, virtual processor scheduler, interrupt and timer management, synchronization routines, partitions (virtual machine instances) management and inter-partition communication (IPC), and more.

Not part of the OS kernel, but exists beneath it when virtualization is enabled.

- Manages

- virtual machines (partitions)

- virtual CPUs

- virtual memory

- interrupt routing

- isolation.

Portability

Windows was designed to run on a variety of hardware architectures. Windows XP and Windows Server 2003 added support for two 64-bit processor families: the Intel Itanium IA-64 family and the AMD64 family with its equivalent Intel 64-bit Extension Technology (EM64T). These latter two implementations are called 64-bit extended systems and in this book are referred to as x64.

Newer editions of Windows support the ARM processor architecture. For example, Windows RT was a version of Windows 8 that ran on ARM architecture, although that edition has since been discontinued. Windows 10 Mobile—the successor for Windows Phone 8.x operating systems—runs on ARM based processors, such as Qualcomm Snapdragon models. Windows 10 IoT runs on both x86 and ARM devices such as Raspberry Pi 2 (which uses an ARM Cortex-A7 processor) and Raspberry Pi 3 (which uses the ARM Cortex-A53). As ARM hardware has advanced to 64-bit, a new processor family called AArch64, or ARM64, may also at some point be supported, as an increasing number of devices run on it.

Windows achieves portability across hardware architectures and platforms in two primary ways.

1- By using a layered design

Windows uses a layered design in its operating system architecture to support portability across different processor architectures and hardware platforms. This design ensures that low-level components that are closely tied to specific CPU architectures or hardware configurations are separated into distinct modules. As a result, the higher layers of the system—such as application services, device drivers, or system utilities do not need to concern themselves with the underlying hardware differences. They interact with standardized interfaces provided by the lower layers.

The two primary components that enable this level of portability are the kernel, which is implemented in the file Ntoskrnl.exe, and the Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL), which resides in Hal.dll. These two modules work together to isolate architecture- and platform-specific functionality from the rest of the system.

The kernel itself handles core OS responsibilities, such as thread context switching, interrupt and exception (trap) dispatching, and synchronization. These are tasks that are inherently dependent on CPU architecture, and so this portion of the kernel includes architecture-specific code to perform them correctly across different processors, such as x86, x64, or ARM.

In contrast, the HAL focuses on abstracting hardware-level differences that exist even within the same CPU architecture for example, variations between different motherboards, chipsets, or bus controllers. By encapsulating this hardware-specific behavior in the HAL, the kernel and other parts of the OS can rely on a consistent interface regardless of the specific hardware configuration beneath.

Aside from the kernel and HAL, only a small portion of the memory manager contains architecture-specific code, which further reinforces the portability of the overall design.

A similar separation of responsibilities applies to the hypervisor, which supports virtualization in Windows. Although it supports both Intel VT-x and AMD SVM hardware virtualization extensions, most of the hypervisor’s internal logic is shared. Only certain components are tailored to the specific processor vendor’s implementation. This is why, on disk, there are two separate files for the hypervisor Hvix64.exe for Intel systems and Hvax64.exe for AMD systems even though much of their functionality overlaps.

This design approach allows Microsoft to maintain a unified operating system codebase that can run on a wide range of hardware platforms with minimal changes, making Windows both scalable and portable.

2- By using C

The Windows operating system is primarily written in the C programming language, which forms the foundation for most of its codebase due to C's balance of low-level control and high-level structure. Some portions of Windows are also written in C++, particularly where object-oriented structures are beneficial, such as in user interface and COM-based components.

Assembly language is used in the operating system only where it is absolutely necessary. This includes two main categories:

-

Direct interaction with hardware, such as when the OS must handle interrupts, traps, or other CPU-specific instructions that cannot be expressed in high-level languages.

-

Performance-critical routines, where speed is essential and writing in assembly yields better performance than compiled C code. A typical example of this is thread context switching, which requires saving and restoring CPU registers very efficiently.

The use of assembly is not limited to the kernel or HAL. It also appears in other parts of the core operating system. For example, some atomic operations (like interlocked increment or compare-and-swap) are implemented in assembly for performance and correctness on multiprocessor systems. Additionally, portions of the Local Procedure Call (LPC) mechanism—used for communication between processes and subsystems—also rely on assembly code for precise, low-level control.

Beyond kernel mode, user-mode components can also include assembly. One key example is the startup code in Ntdll.dll, which is one of the first libraries loaded in any Windows process. This startup code is responsible for setting up the execution environment before handing over control to the application’s main function.

Conclusion

Windows exemplifies practical computer architecture through strict privilege separation, layered modularity, and hardware abstraction. Its design isolates architecture-specific code in the kernel and HAL, enabling seamless portability across x86, x64, and ARM platforms. By relying primarily on C with minimal assembly, it achieves high performance and maintainability. Ultimately, Windows transforms theoretical concepts into a robust, real-world system that balances security, compatibility, and evolution across decades.