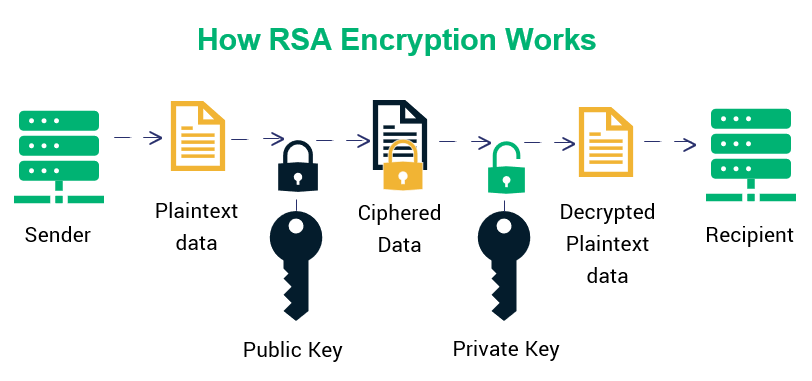

Part 4: RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) Encryption Algorithm

The "Big Number Factoring" Lock

The Core Insight

RSA's security rests on a single mathematical fact: Multiplying two large prime numbers together is trivially easy. Factoring the result back into the original primes is computationally impossible.

RSA Key Generation: Step by Step

Step 1: Pick Two Large Prime Numbers

In real systems, each prime is roughly 1,024+ digits long (cryptographers call this "1024-bit").

For illustration, let's use tiny primes:

p = 61

q = 53

Step 2: Multiply Them

n = p × q = 61 × 53 = 3,233

This number n = 3,233 is your public key component. It's used to encrypt messages for you.

In real RSA, n is a 600+ digit number. Factoring that back into the original primes would take billions of years on a classical computer.

Step 3: Calculate a "Magic Number" Based on the Primes

There's a mathematical calculation (Euler's totient) that depends on p and q:

For our example: φ(n) = (p-1) × (q-1) = 60 × 52 = 3,120

This number is used internally but never shared.

Step 4: Choose Your Public Exponent `e`

This is almost always 65,537 (chosen for efficiency). It must be chosen so that it doesn't share common factors with φ(n).

For our example: e = 17

Your public key is now: (n=3,233, e=17)

Anyone can have this. It's safe to post on your website.

Step 5: Calculate Your Private Exponent `d`

Using mathematical calculations, find a number `d` such that when you use it with `e`, they "undo" each other in a special way.

For our example: d = 2,753

Your private key is now: (n=3,233, d=2,753)

Critical: Destroy p, q and φ(n) completely. They're only used for key generation.

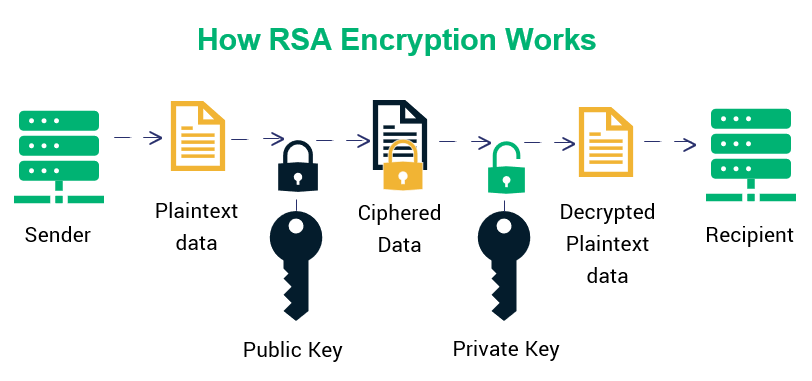

RSA Encryption: Sending a Secret Message

Alice wants to send the letter "A" to Bob.

Step 1: Bob Shares His Public Key

Bob publishes: (n=3,233, e=17)

Step 2: Alice Converts Her Message to a Number

The letter "A" in ASCII is 65.

Step 3: Alice "Raises" the Message to the Power of `e`, Then Takes the Result Modulo `n`.

Conceptually (simplified): ciphertext = messagee mod n

In our example:

6517 mod 3,233 = 2,790

Step 4: Alice Sends the Ciphertext

Alice sends: 2,790

An eavesdropper sees:

- Ciphertext: 2,790

- Public key: (n=3,233, e=17)

- But cannot decrypt without `d`

RSA Decryption: Only Bob Can Read It

Step 1: Bob Receives the Ciphertext

Bob receives: 2,790

Step 2: Bob Uses His Private Exponent `d`

Bob computes: plaintext = 2,7902,753 mod 3,233 = 65 = "A"

Bob recovers the original message.

Why Can Only Bob Decrypt it:

To decrypt, an attacker would need to find `d`.

To find `d`, they'd need φ(n) = 3,120.

To find φ(n), they'd need to factor n = 3,233 back into p = 61 and q = 53.

With our tiny numbers, factoring is easy:

- Try dividing 3,233 by small primes

- Eventually find that 3,233 = 61 × 53

But with real RSA-2048 (600-digit `n`), there are no efficient classical algorithms to factor it. The best known methods would take billions of years.

Real World Applications of RSA:

1. HTTPS Certificates

Your browser trusts HTTPS because of RSA signatures on certificates:

1. Certificate Authority (CA) has an RSA key pair

2. When you request an HTTPS certificate for example.com,

the CA verifies you own the domain

3. The CA signs your certificate with their private key

4. Your certificate is sent to browsers

5. Browsers verify the signature using the CA's public key

(shipped with the browser)

6. If the signature is valid, the browser trusts your identity

This chain of trust is how HTTPS knows you're actually communicating with Amazon, not an attacker.

2. TLS Key Exchange (Older Protocol)

Older TLS versions used RSA for key exchange (TLS 1.2 and earlier allowed it):

1. Client has server's public key from certificate

2. Client generates a 256-bit symmetric key

3. Client encrypts it with server's RSA public key

4. Server decrypts it with its RSA private key

5. Both have the symmetric key; now use AES for data

Modern TLS 1.3 abandoned this because it's slower than elliptic curve key exchange (coming next).

3. Code and Document Signing

Developers sign code with RSA to prove they wrote it:

1. Developer hashes their code (produces a unique fingerprint)

2. Developer encrypts the hash with their RSA private key (creates signature)

3. User downloads code + signature

4. User verifies signature using developer's public key

5. If valid, code is authentic and unaltered

RSA: Practical Numbers

- Typical key size: 2,048 bits (256 bytes) for current security

- Future recommendation: 4,096 bits (512 bytes) for long-term security

- Signature size: 256 bytes

- Encryption overhead: Requires padding, so actual data is smaller

- Speed: Slower than symmetric crypto (used only for key exchange and signatures)

Part 5: Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) – The "Compact, Efficient" Alternative

Why ECC Exists

RSA works perfectly but has one problem: large key sizes.

To achieve 256-bit security (equivalent to AES-256):

- RSA: Need ~15,000-bit keys (1,875 bytes)

- ECC: Need ~256-bit keys (32 bytes)

ECC is 60× smaller for identical security.

This matters for:

- Mobile devices with limited storage

- IoT devices with minimal processing power

- Bandwidth constraints

- Speed (smaller keys = faster operations)

Modern systems strongly prefer ECC: TLS 1.3, Signal, WhatsApp, Bitcoin, Ethereum, and modern APIs all use ECC.

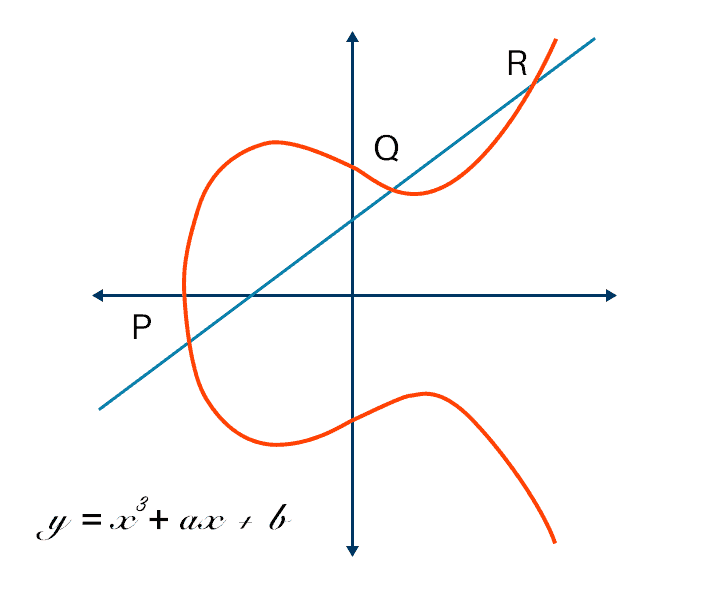

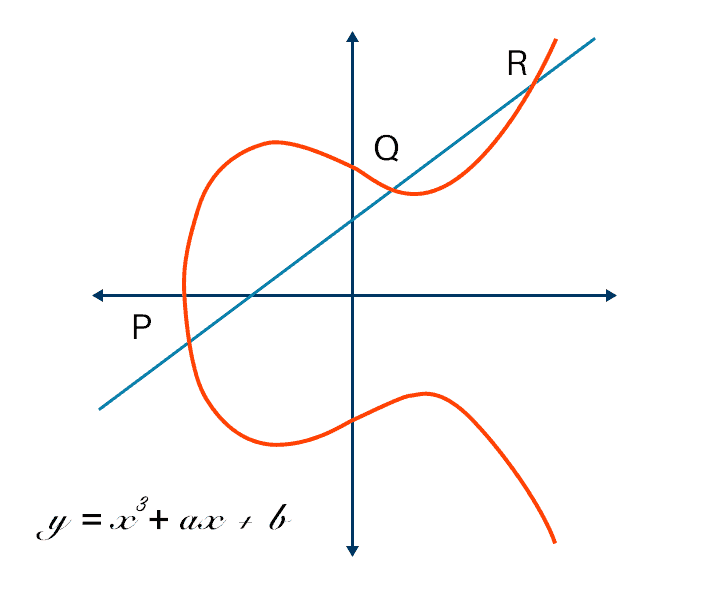

The Elliptic Curve: A Geometric Concept

An elliptic curve is a curve defined by the equation:

y = x³ + ax + b

Where:

- a and b are constants chosen for the specific curve

- All arithmetic happens in a finite field (modulo a large prime)

- The curve contains thousands of billions of points

The special property: You can define an "addition" operation on points of this curve that creates a group structure.

How "Addition" Works on Elliptic Curves

This isn't normal addition. Here's the geometric idea:

1. To add point P to point Q:

- Draw a line through P and Q

- The line intersects the curve at a third point R

- Reflect R across the x-axis

- That reflection is your result: P + Q

2. To add a point to itself (P + P):

- Draw a tangent line to the curve at P

- The tangent intersects the curve at another point R

- Reflect R across the x-axis

- That's your result: 2P

3. To add P multiple times:

- P + P + P = 3P (add P to itself 3 times)

- Conceptually: kP = P + P + ... + P (k times)

The key insight: You can easily compute `kP` (P added to itself k times), but if someone gives you `kP` and `P`, finding k is computationally infeasible.

This is the Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP), and it's the foundation of ECC security.

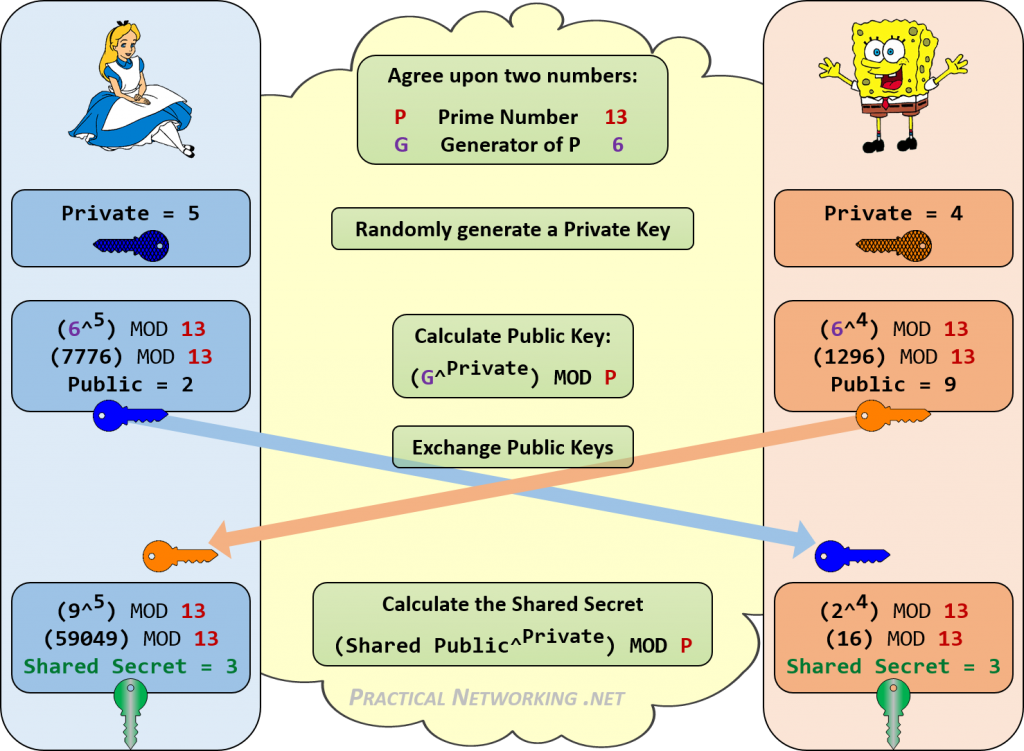

ECDH: Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman Key Agreement

ECDH solves the key exchange problem using elliptic curves.

Setup (Public Knowledge)

Alice and Bob agree on:

- A specific elliptic curve (like Curve25519 or P-256)

- A starting point 'G' on that curve

The Protocol

Alice's Side:

1. Pick a random private number: a = 42 (only Alice knows this)

2. Compute her public key by adding P to itself 42 times: A = 42G

3. Send A to Bob over the open network

Bob's Side:

1. Pick a random private number: b = 17 (only Bob knows this)

2. Compute his public key by adding G to itself 17 times: B = 17G

3. Send B to Alice over the open network

Alice's Computation of Shared Secret:

1. Receive Bob's public key: B = 17G

2. Multiply it by her private key: S = 42 × B = 42 × (17G)

3. Result: S = (42 × 17) × G = 714G

Bob's Computation of Shared Secret:

1. Receive Alice's public key: A = 42G

2. Multiply it by his private key: S = 17 × A = 17 × (42G)

3. Result: S = (42 × 17) × G = 714G

The Magic: Both Alice and Bob computed the same point '714G'!

Why an Eavesdropper Can't Compute It

An attacker sees:

- Alice's public key: 42G

- Bob's public key: 17G

- But doesn't have 42 or 17

To compute the shared secret 714G, they'd need to either:

- Find 42 from 42G (solving ECDLP), or

- Find 17 from 17G (solving ECDLP)

Both are computationally infeasible.

ECDSA: Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm

ECDSA is the ECC equivalent of RSA signatures. It's used to sign:

- HTTPS certificates

- Software updates

- Bitcoin transactions

- Legal documents

Signing a Document

Bob wants to sign a message to prove he created it.

Step 1: Bob hashes the message (produces a unique fingerprint)

Example:

hash("I authorize this payment") = 789

Step 2: Bob generates a random nonce k

Example:

k = 55 (used only once, then discarded)

Step 3: Bob computes a point on the curve using k

- Point = 55G (add G to itself 55 times)

- Extract x-coordinate of this point, call it r

- r = (x-coordinate of 55G) mod curve_order

Step 4: Bob creates the signature combining his private key, the hash, and `r`

s = k^-1 × (hash + r × private_key) mod curve_order

s = 55^-1 × (789 + r × bob's_private_key) mod curve_order

(^-1 means "modular inverse" - a specific mathematical operation)

Step 5: Signature is the pair (r, s)

Verifying the Signature

Alice receives Bob's message and signature (r, s).

Step 1: Alice hashes the message herself

hash("I authorize this payment") = 789 (same as Bob)

Step 2: Alice performs a calculation using:

- The signature values r and s

- The message hash

- Bob's public key

Point = (s^-1 × hash × G) + (s^-1 × r × bob_public_key)

Step 3: Extract the x-coordinate of this point

Step 4: If the x-coordinate equals r, the signature is valid!

Why Forgery is Impossible

To forge Bob's signature, you'd need to create a valid (r, s) pair without knowing Bob's private key.

This is mathematically equivalent to solving ECDLP (finding the private key from the public key).

With Curve25519 or P-256, this is computationally impossible.

Curve Selection: What's Actually Used

- P-256 is used in: iPhones, Android, TLS certificates, government systems, NIST standard; some debate about design transparency.

- Curve25519 is used in: Signal, WireGuard VPN, modern TLS | Designed for security and resistance to implementation errors.

- secp256k1 is used in: Bitcoin, Ethereum | Chosen for efficiency, not part of NIST standards.

- P-384, P-521 is used in: High-security applications | Larger curves for 192-bit and 256-bit security levels.

Part 6: Modern TLS – Symmetric, Asymmetric, and Hash Functions Working Together

To understand why quantum computers are a threat, you need to see how these three cryptographic tools work together in practice.

A Real HTTPS Connection: Step by Step

When you visit 'https://amazon.com', here's exactly what happens:

Step 1: ClientHello

Your browser initiates a connection:

"Hi Amazon, I'd like a secure connection.

I support these elliptic curves: P-256, Curve25519, etc.

I support these symmetric ciphers: AES-128-GCM, AES-256-GCM, ChaCha20-Poly1305"

The browser also sends its ephemeral public key (generated fresh for this connection).

Step 2: ServerHello

Amazon responds:

"Great! I've chosen:

- Elliptic Curve: Curve25519

- Symmetric Cipher: AES-256-GCM

Here's my certificate with my long-term public key

Here's my ephemeral public key for this session"

Amazon also includes a digital signature on the handshake messages (using ECDSA).

Step 3: Certificate Verification

Your browser receives Amazon's certificate and checks:

1. Is this certificate signed by a trusted CA?

- Your browser has the CA's public key

- Uses ECDSA verification to check the signature is valid

- If valid, the CA approved Amazon's identity

2. Does the domain name match?

- Certificate says: "This is for amazon.com"

- URL bar shows: "amazon.com"

- Match? ✓

3. Is it expired?

- Certificate says: "Valid until 2025-12-15"

- Today is: 2025-12-04

- Valid? ✓

If all checks pass, the browser trusts Amazon's identity.

Step 4: ECDH Key Agreement

Your browser now has:

- Amazon's ephemeral public key (from ServerHello)

- Your ephemeral private key (generated in Step 1)

Both you and Amazon compute the same ECDH shared secret:

Your computation: your_private_key × amazon_ephemeral_public_key = SHARED_SECRET

Amazon's computation: amazon_private_key × your_ephemeral_public_key = SHARED_SECRET

(These are identical due to elliptic curve math)

Critical: This ECDH secret is temporary—it's destroyed after the connection closes.